Suggested reading:

Up-to-date

Overview:

Up-to-date

Up-to-date

Step one: verify tachycardia and hemodynamic stability. If unstable refer to ACLS algorithms please.

Step two: determine whether the QRS is narrow complex or wide complex

Step three: if narrow complex determine whether irregular or regular rhythm

Step four: if wide complex tachycardia, determine whether monomorphic or polymorphic

ECG: electrocardiogram; AVNRT: atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; AVRT: atrioventricular reciprocating (bypass-tract mediated) tachycardia; AT: atrial tachycardia; SANRT: sinoatrial nodal reentrant tachycardia; AF: atrial fibrillation; AV: atrioventricular; VT: ventricular tachycardia; SVT: supraventricular tachycardia; WPW: Wolff-Parkinson-White.

* A narrow QRS complex is <120 milliseconds in duration, whereas a wide QRS complex is ≥120 milliseconds in duration.

¶ Refer to UpToDate topic reviews for additional details on specific ECG findings and management of individual arrhythmias.

Δ Monomorphic VT accounts for 80% of wide QRS complex tachycardias; refer to UpToDate topic on diagnosis of wide QRS complex tachycardias for additional information on discriminating VT from SVT.

Estimate using “300, 150, 100…”

Bradycardia: rate = cycles/6 sec. strip × 10

Identify basic rhythm, scan for prematurity, pauses, irregularity, abnormal waves. Check for:

QRS above or below baseline for Axis Quadrant (Normal vs. R. or L. Axis Deviation).

Find isoelectric QRS in a limb lead for Axis in degrees using the “Axis in Degrees” chart.

Axis rotation (horizontal plane): find “transitional” (isoelectric) QRS.

Check P wave (atrial hypertrophy).

Check R wave in V₁ (Right Ventricular Hypertrophy).

Check S wave depth in V₁ and R wave height in V (Left Ventricular Hypertrophy).

Scan leads for:

Q waves

Inverted T waves

ST segment elevation/depression

Find location of pathology and identify the occluded coronary artery.

Determine rate by observation using the triplet method (300-50).

Fine division/rate association reference chart provided.

100/min = Sinus Tachycardia

<60/min = Sinus Bradycardia

Determine independent (atrial/ventricular) rates if co-existing rhythms are present

Identify basic rhythm, then scan tracing for pauses, premature beats, irregularity, and abnormal waves.

Always check: P before each QRS, QRS after each P; PR intervals, QRS interval; QRS vector shift outside normal range

An unhealthy Sinus (SA) Node fails to emit a pacing stimulus (“Sinus Block”).

A sick Sinus (SA) Node may cease pacing (“Sinus Arrest”).

Escape Beats can be: Atrial, Junctional, or Ventricular.

Premature Beats can be: Atrial, Junctional, or Ventricular.

Paroxysmal – rate: 150-250/min.

Flutter – rate 250-350/min

Fibrillation – rate 350-450/min

1st AV Block: Prolonged PR interval

2nd AV Block: Some P waves without QRS response

Wenckebach

Mobitz

3rd AV Block: No P wave produces a QRS response

if the QRS is positive in I and AVF = Normal

Axis in Degrees

After locating the Axis Quadrant, find the limb lead where QRS is most isoelectric

Find transitional (isoelectric) QRS in a chest lead

Right Atrial Hypertrophy: Large, diphasic P wave with tall initial component

Left Atrial Hypertrophy: Large, diphasic P wave with wide terminal component

Right Ventricular Hypertrophy

Left Ventricular Hypertrophy

Always obtain patient’s previous EKG’s for comparison!

Know Coronary Artery Anatomy.

Posterior

Lateral

Inferior

Anterior

Pulmonary Embolism

Artificial Pacemakers

Electrolytes:

Potassium

Calcium

Digitalis

Quinidine

Dubin’s Quickie Conversion: Patient’s weight in kg. = Half of patient’s wt. (in lb.) minus 1/10 of that value.

Modified Leads for Cardiac Monitoring.

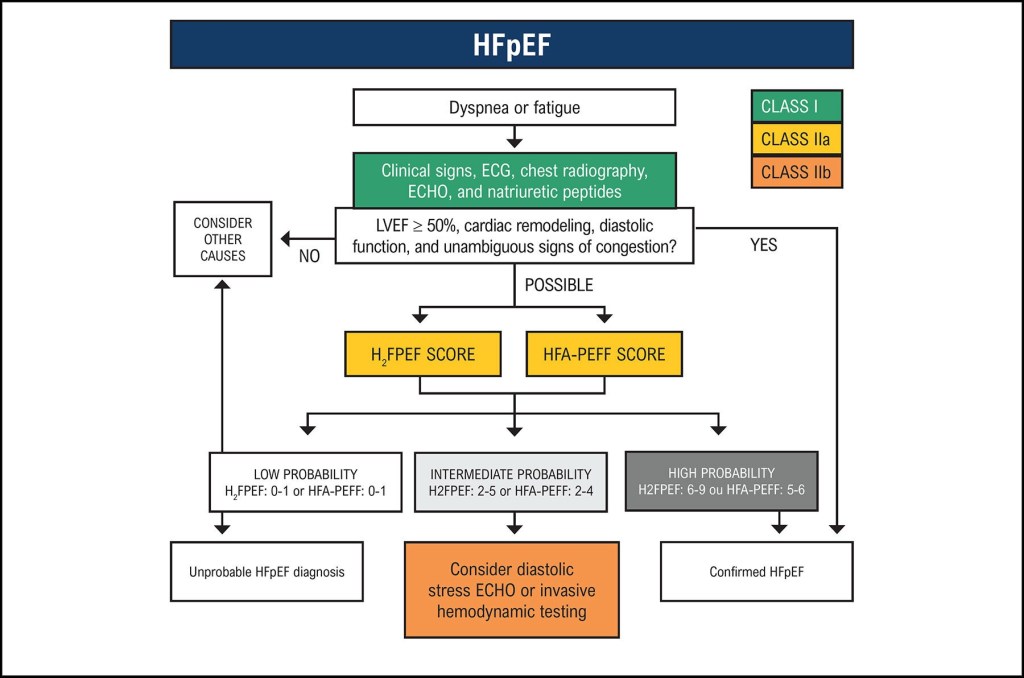

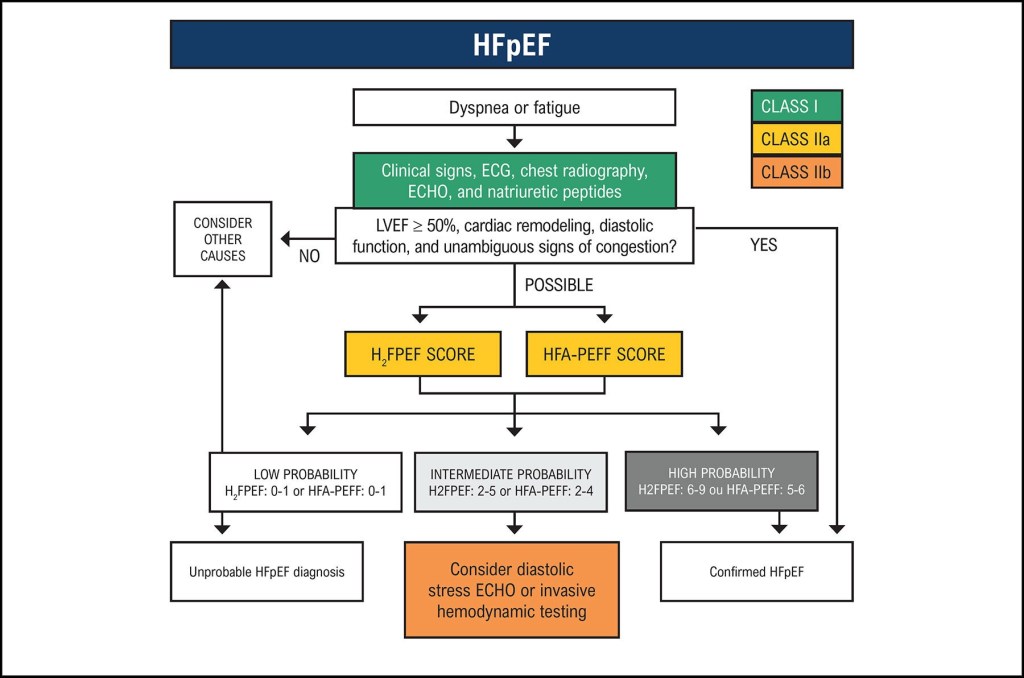

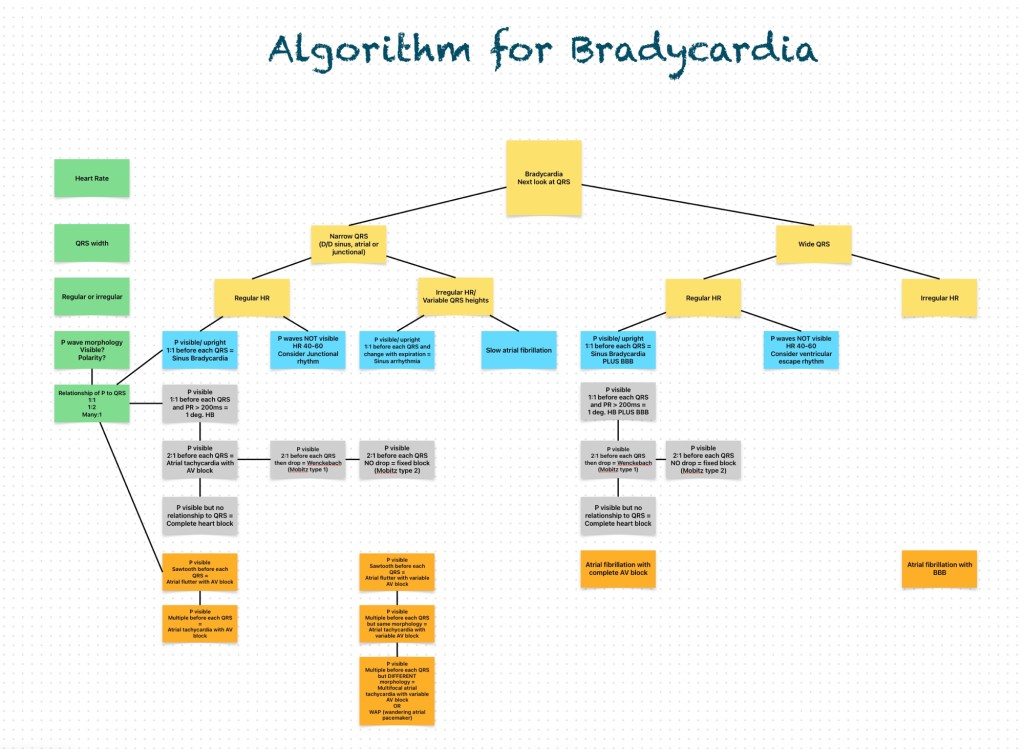

Here is the algorithm for bradycardia

Edema evaluation

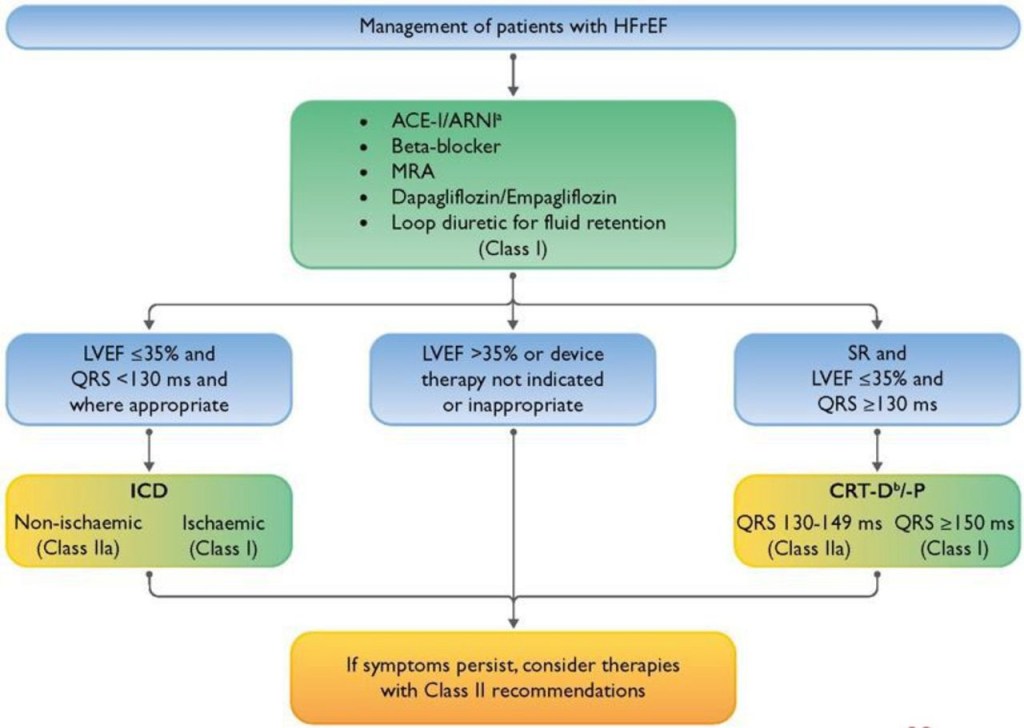

Please see the “Guidelines” section.

Please use the text of your choice, e.g., UpToDate, Step-up to Medicine, Harrison’s, etc.

Dyspnea

Chest pain Continue reading

Comment: In large trials published in 2005 and 2010, fenofibrate did not improve cardiovascular outcomes significantly in patients with type 2 diabetes (JW Cardiol Jan 5 2006 and Mar 14 2010). Although gemfibrozil lowered rates of cardiovascular endpoints in older trials involving high-risk nondiabetic patients conducted largely before the statin era — for example, the Helsinki Heart Study (JW Gen Med Nov 17 1987) and VA-HIT Trial (JAMA 2001; 285:1585) — most such patients would now receive statins as first-line therapy. Thus, the recent rapid expansion of fenofibrate prescribing is unwarranted. One reason for this phenomenon is aggressive marketing of fibrates; another is confusion among clinicians about the lack of hard evidence to support add-on triglyceride-lowering therapies in patients receiving statins.

Prescribing of Fibrates Is Booming in the U.S. – General Medicine.